Image Credit | Raymond Clinkscale

Tuberculosis (TB) is likely the world’s leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). In 2023, 10.8 million people fell ill, and 1.25 million people died from TB, which is a curable and preventable disease of poverty.

We sat down with Stephan Schwander, associate professor at the Rutgers School of Public Health, ahead of World TB Day to raise awareness for the disease and highlight ongoing research and efforts to eradicate it.

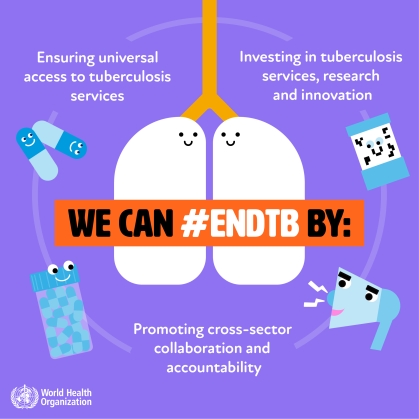

World TB Day is commemorated annually on March 24 to raise public awareness of the “devastating health, social, and economic consequences of TB.” This year’s theme is “Yes! We can end TB: Commit, Invest, Deliver,” which aims to serve as a call for hope, urgency, and accountability by the World Health Organization. You can find additional resources, challenges, and information by visiting WHO’s World TB Day website.

---

What sparked your interest in tuberculosis research, and what specific area do you focus on?

My interest in TB research was not sparked by a single event but rather by repeated encounters with patients and the complexity of their disease during my time as a medical student, clinical physician, and now a translational researcher. As a medical student and physician, I saw firsthand how TB was deeply intertwined with poverty, poor living conditions, and malnutrition. These experiences, combined with my clinical and translational research experience, fueled my commitment to studying TB.

My journey began during a six-month medical internship in Peru, where TB was prevalent. Later, at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, I became involved in clinical research on HIV therapy, focusing on the treatment of TB in HIV-coinfected individuals. This work led me to Uganda, where I conducted a randomized, double-blind antituberculosis treatment trial in HIV-infected persons at a time when HIV antiretroviral therapy was unavailable.

My research expanded as I pursued postdoctoral studies at Case Western University, delving into the immune system’s response to TB, particularly in the context of untreated HIV infection. I also spent extended time in Mexico City at the National Institutes for Respiratory Diseases (INER), where I discovered microscopic inclusions of air pollution particles in alveolar macrophages, prompting new research questions, which included investigating the impact of air pollution on immune defenses against Mtb, the bacterium that causes TB.

My current research, funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, has refocused on Uganda, a WHO-defined high TB burden country. With colleagues at Makerere University, University of Leicester, McGill, and Rutgers, we study whether air pollution exposure influences household and community transmission of Mtb and the susceptibility to the infection. Our study is based on experimental evidence that air pollution particles suppress immune defenses against Mtb and employs innovative breath-sampling masks and advanced personal air pollution assessments to understand these dynamics in Kampala’s Namuwongo informal settlement, where the average daily income is below two U.S. dollars. Our community and environmental health worker staff are from the Namuwongo community and are led by a community NGO (EASE Uganda). With two billion people living in similar low-income conditions worldwide, this research has significant global public health implications.

What are the most pressing issues in TB control and prevention today?

The most pressing issue is the political will to end TB, alongside sustained financial support for global TB control programs, as well as the recognition that “TB anywhere is TB everywhere.” TB remains a global health crisis and a significant cause of death among individuals with AIDS. Despite being treatable, drug-resistant TB is on the rise due to the lengthy and complex treatment regimen, which increases the likelihood of errors and incomplete treatment.

Strengthening global TB control programs requires a focus on diagnostics and treatment delivery but also addressing the social determinants of TB. Ending poverty and reducing environmental risks perpetuating Mtb transmission would strongly contribute to TB control.

Continued research is critical. We still don’t understand enough how our immune defense responses, together with Mtb strain differences, influence the course of an infection and the transmission of Mtb between persons. Such information is required in the context of TB vaccine design and identifying biomarkers that could help guide therapeutic or prophylactic interventions. A new TB vaccine for adults and improved diagnostics and treatment options are urgently needed.

Strengthening TB control efforts also requires addressing the social determinants of TB—poverty, malnutrition, and environmental factors like air pollution—that seem to increase progression to and rates of active disease.

My research explores whether the environment and air pollution modify the transmission of Mtb in low-income communities where TB incidence rates tend to be high. While epidemiological studies show that household and ambient air pollution exposures increase the rate of new TB, it is not yet understood if air pollution exposure modifies or facilitates the transmission of Mtb. Interrupting the transmission of Mtb is a significant goal in ending TB. In low- and middle-income countries, low-income communities often reside in informal urban settings. In these settings, the risk of being exposed to household air pollution from the combustion of solid biomass (e.g., wood, charcoal, dung) during cooking and heating is high—cleaner fuels for cooking need to be made available. Household air pollution is compounded by ambient urban air pollution from vehicular traffic, industries, resuspended soil, and dust from winds and storms.

Funding needs to continue and be increased. In the U.S., past TB resurgences have been linked to declines in TB control programs and rising global cases. The WHO has warned that recent cuts to USAID funding could contribute to a worldwide TB surge. The disease disproportionately affects marginalized, low-income populations, where TB stigma further impedes access to early diagnosis and treatment.

What recent advancements have been made in TB diagnostics and treatment?

Significant progress has been made in the past two decades. The PCR-based Gene Xpert test, developed at the New Jersey Medical School, allows for faster and more precise TB detection, including antibiotic resistance profiling. Additionally, point-of-care urine LAM tests have become crucial for diagnosing TB in individuals with HIV co-infection.

On the treatment front, new drug regimens can shorten TB treatment time from six to three months, making adherence easier and reducing the risk of drug resistance; however, these regimens are not widely available. Promising TB vaccine candidates also undergo clinical trials, offering hope for more effective prevention strategies.

What strategies are most effective for TB control in high-burden countries?

The essential tools to eliminate TB already exist, but their success depends on strong political commitment, continued and increasing funding for global TB control, global collaboration, and universal healthcare access. Interruptions in TB services, such as those seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in over 700,000 excess TB deaths between 2020 and 2023, highlighting the consequences of underfunding.

Beyond medical interventions, broader social and environmental measures are needed. Improving nutrition, housing, and environmental conditions—especially in low-income urban areas—can significantly reduce Mtb transmission. Addressing air pollution (a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment is a human right) and assuring adherence to air quality guidelines, for instance, may play a critical role in TB control by improving lung health and immune resilience.

What do you think is the most underexplored area in TB research?

One of the least understood aspects of TB is the transmission dynamics of Mtb and the factors influencing disease progression in the world we now live in. For example, recent data suggests that air pollution exposure may enhance Mtb transmission, a globally relevant hypothesis. The California wildfires, for instance, have been linked to increased numbers of new TB cases in the state.

Additional climate change effects, such as food insecurity and increased global migration, are emerging TB control challenges. Understanding how these factors intersect with Mtb transmission and disease progression will be crucial in shaping targeted prevention and treatment strategies.