TW: The article below addresses suicide and death.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

---

September is Suicide Prevention Month – a time to raise awareness of this urgently important crisis. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) uses this month to shift public perception, spread hope, and share vital information with people affected by suicide. Their goal is to ensure that individuals, friends, and families have access to the resources they need to discuss suicide prevention and to seek help.

We sat down with Dr. Joye Anestis, a licensed clinical psychologist and associate professor in the Rutgers School of Public Health’s Department of Health Behavior, Society, and Policy, to discuss her suicide prevention research and work. Dr. Anestis also leads the school’s Population Mental Health concentration.

Can you share a bit about your background and what led you to specialize in suicide risk assessment and prevention?

I’m a native Mississippian and a licensed clinical psychologist. I received my PhD in Clinical Psychology from Florida State University (FSU), where I entered my doctoral program with a variety of research interests… none of which were suicide.

Suicide became part of my research program in a roundabout way. As part of my doctoral work, I was enormously fortunate to be a trainee therapist at the FSU Psychology Clinic, which was (and still is) directed by Dr. Thomas Joiner. Dr. Joiner is one of the most important suicide researchers in the world, and suicide risk assessment and prevention was a core part of our clinical training. Dr. Joiner impressed upon us the importance of not being scared to talk about suicide with clients but approaching the topic straightforwardly and matter-of-factly. He emphasized that this approach was critical in decreasing shame and stigma around suicide and that it was not only important in clinical work but in the rest of our lives as well. This lesson has stayed with me and continues to impact how I interact with the world.

At the FSU Psychology Clinic, I provided psychotherapy to a variety of individuals, including many who were struggling with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. I learned to use dialectical behavior therapy (commonly known as DBT), a gold standard evidence-based treatment for suicidal thoughts and behaviors, to help them. These clinical experiences, and the influence of Dr. Joiner and his willingness to have me as an eventual research collaborator, led me to begin incorporating suicide risk assessment and prevention into my research portfolio.

September is Suicide Prevention Month. What are some common misconceptions about suicide that you think need more public awareness?

There is an abundance of misconceptions about suicide that are commonly held in society that we know do a ton of harm. There is a great book called Myths About Suicide by Dr. Joiner that I’d recommend if someone wanted to learn more.

One major misconception is the sentiment along the lines of “if someone really wants to die by suicide, we can’t stop them” – the idea that there is no point intervening in someone’s suicidal behavior because they will “just find another way.” Imagine if your loved one was at risk for a heart attack, stroke, or some other serious illness, and the public response was, “Why bother intervening? They are just going to die anyway.”

The data clearly shows that this belief is extremely inaccurate and harmful, and it has greatly impeded the adoption of population-level prevention strategies that we know would make a big impact. Research has shown that among those who survive a suicide attempt, 75% will never attempt suicide again, and 90% will never ultimately die by suicide. So, in a very real way, if we prevent someone from attempting suicide using a specific method at a specific time point, it is substantially likely that we are preventing them from ever attempting suicide by any method in the future.

If more people understood this as a society, we would be more open to suicide prevention strategies that would make the biggest difference on a population level. Such as implementing strategies like “lethal means safety,” which refers to intentional efforts to remove access to or reduce the lethality of objects that can be used to inflict self-directed violence.

What role does stigma play in suicide prevention, and how can we work towards reducing it, especially in marginalized communities?

Stigma is a major barrier to suicide prevention. People experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors often feel shame and avoid disclosing their struggles with others. Our society can also be very shaming and judgmental toward people with histories of suicide. I bet you can pretty easily think of negative things you have heard people say about someone who died by suicide or survived a suicide attempt, like “they are a coward” or “they took the easy way out.”

All these judgments are misconceptions. There is nothing easy about self-harm, and lots of research has shown this. These beliefs prevent people from asking for help, and they also prevent society from demanding programs and policies to help people and decrease suicide rates.

We can’t do anything about something we don’t talk about.

Stigma about suicide is pervasive across all communities, but cultural norms about problem-solving, disclosing emotions and other private experiences, and seeking help vary. If we want to help everyone, we must ensure we are developing efforts that are sensitive to these differences. Furthermore, we must be aware of the reality that some communities have experienced harm from the mental healthcare system and understandably don’t trust us as a solution to important problems.

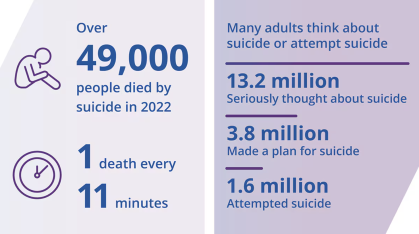

Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide. In 2022, over 49,000 people in the U.S. died by suicide – that’s one person every 11 minutes. A 2019 study estimated that, for each suicide, 135 people are exposed to death. That’s nearly 6 million people exposed to suicide annually. Not to mention the estimated 13.2 million adults who seriously think about suicide each year. So, each one of us knows someone who thinks about suicide – whether they’ve told us or not. This is an issue that affects all humans.

One way to work toward reducing stigma is to talk about it the way Dr. Joiner trained us to do – straightforward, matter-of-fact, and without fear. For example, if you are a parent of a teen, suicide should be one of “the talks” you have with them. Let them know that if they are struggling, you are a safe person to tell; have them save the 988 Lifeline as a contact in their phone; come up with a plan about what they could do if they have a friend who is talking about suicide (tell you, tell their parents).

As we look to the future, what are some of the emerging trends or challenges in suicide prevention that you believe will be critical to address?

One critical challenge that needs to be addressed is the role of firearms in suicide.

The majority of firearm deaths in this country are suicides. Firearm policy is, of course, extremely challenging and contentious in the U.S. However, policies that support the secure storage of firearms are critical in reducing suicide deaths.

Secure storage means storing firearms unloaded, locked, and separate from ammunition. This is the idea of “lethal means safety” that I mentioned earlier. We as a society are comfortable with means safety in other ways – we all wear seatbelts in our cars, as just one example. The movement in the 1980s and 1990s to stop drunk driving is another example (“friends don’t let friends drive drunk”).

Safe storage of firearms would prevent someone from attempting suicide using that specific method at a specific time point and, therefore, likely prevent them from ever attempting suicide by any method in the future. If society embraced this idea and policy supported it, just like what happened with automobile safety, the number of lives saved would be enormous.

If there was one key message you could share with everyone during Suicide Prevention Month, what would it be?

It is hard for me to pick just one! So many messages are needed! But I’ll go with: Just one small gesture of connection can make a big difference.

Caring contacts – personalized communication in writing expressing interest and concern for someone’s well-being without placing demands for a response or action – have been repeatedly shown to decrease suicide attempts and deaths. It sounds too basic, but it’s true – social connection is magical.

It can be as simple as sending someone a text message saying, “Hey, you were on my mind. I hope you are well.” Try it now – who knows the difference it might make.

Resources

Rutgers Health Resources

Rutgers Health provides access to crisis intervention services, counseling and therapy, peer support, and support groups for all members of our community:

NJ Specific Mental Health Community Resources

- If you are not in crisis but need to talk, you can call New Jersey's Peer Recovery WarmLine at 877-292-5588 (Hours M-F 8 am - 10 pm, Sa-Su 5 pm - 10 pm, holidays 3 pm - 10 pm) here: https://www.mhanj.org/

- For psychiatric emergency care, go to a hospital emergency room or call your county crisis center here: https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dmhas/home/hotlines/MH_Screening_Centers.pdf

- NJ Hopeline – call 855-654-6735 or 9-1-1 or visit here for more information about NJ’s suicide prevention resources here: https://njhopeline.com/

- NJ Chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP): https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dmhas/home/hotlines/MH_Screening_Centers.pdf

National Resources

- The 988 Lifeline is available via phone, text, or chat 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year: https://988lifeline.org/. It is free and accessible to everyone. It is offered in Spanish and ASL, and specialized support is available for veterans/services members and their loved ones and for sexual and gender diverse young people.

- Now Matters Now: https://nowmattersnow.org/

- BlackLine: 1-800-604-5841 – BlackLine provides a space for peer support, counseling, witnessing, and affirming the lived experiences to folxs who are most impacted by systematic oppression with an LGBTQ+ Black Femme Lens.

- Trans LifeLine (Transgender Suicide Hotline): 877-565-8860 (available 24/7)

- Trevor Project (for LGBTQIA support): 1-866-488-7386 (available 24/7)

- NAMI HelpLine: available Monday-Friday 10am-10pm

- Phone: 1-800-950-6264

- Text: 62640

- Email: helpline@nami.org

- Pause to Protect: Resources for individuals and businesses on firearm suicide prevention here: https://pausetoprotect.org/

- If Someone Tells You They are thinking about Suicide (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention) here: https://talkawaythedark.afsp.org/thinkingaboutsuicide

- How to Ask Someone About Suicide (National Alliance on Mental Illness) here: https://www.nami.org/suicide/how-to-ask-someone-about-suicide/

- Practicing Self-Care, Step-by-Step (The Trevor Project): https://www.thetrevorproject.org/blog/practicing-self-care-step-by-step/?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjw3P-2BhAEEiwA3yPhwPXxutf-SHZORGVPo2D2Cm43pZxxuYXUSlhwr8lKuwPLRFGuV9In7xoCCKAQAvD_BwE